Undulations: On Forms That Find Their Way

It was over a bowl of bucatini that I solved a big kiln problem on my first commission. In over my head on this Gehry project next to the Brandenburg Gates, I had barreled ahead—youthfully crossing off problems—when it dawned on me that my clever solution would take nine months when I only had three and would demand a second workshop just to hold the thirty-six car-sized molds. I persisted in thinking that if I just worked harder and longer or differently I could solve it all, until I couldn't. Vanquished, I yielded to the reliable comfort of making a dinner of noodles. Alone at the table, staring into the black walnut tree, a direction came into view.

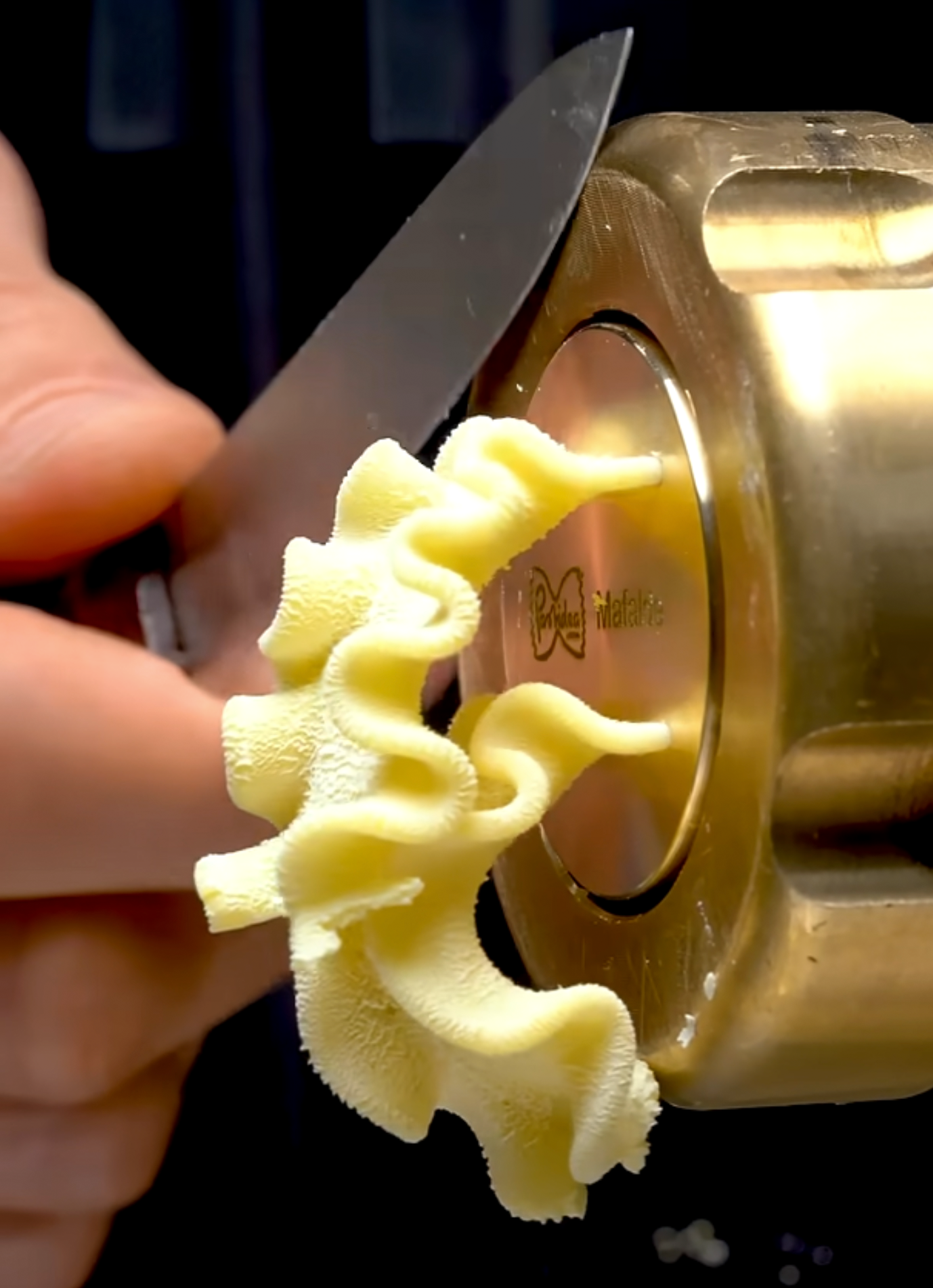

Starting a new project rarely begins for me with a fully formed image. It's a lurching process, reworking old ideas, crumpling one after another. It's only when I withdraw—when intention loosens its grip—that, days later and over a bowl of pasta, a path forward reveals itself. More recently, the muse visited in the form of mafalda with those wild undulating edges.

When making pasta, one can vary flours not only to change flavor and texture but also to solve for different mechanics: delicate ravioli are made from laminated doughs of soft wheat, while extruded shapes are made from Durum wheat tough enough to be forced under high-pressure through small openings in a die. These dies are deceptively simple—when made from teflon they produce slippery spaghetti and from bronze they produce a burred surface that holds sauce better. Similarly, small changes in their machined geometry can produce profound changes in the forms they express. The mafalde die is elegantly simple: the center section is thicker than the edges. As dough is forced through, the thin edges extrude faster, emerging longer than the slower-moving thick center. That mismatch in length forces the ribbon to fold and undulate.

Once I saw it, I started seeing it everywhere. Cuttlefish wings undulating through water. Leaf edges that ruffle and fold. Nudibranchs. Flowers. Fashion—Marilyn's skirt blowing up from the subway draft, where the waist is small but the hem is much longer, creating all those folds in the extra material. It's a fundamental principle that expresses itself in many different forms.

Photo: Rick Heydel

Photo: Sam Shaw

Why Undulations Work

Undulations aren't just pretty—they're solving real problems, and how they look is about what they do. In leaves, ruffled edges create more surface area for photosynthesis and gas exchange. In shells, corrugations provide structural stiffness while minimizing thickness—allowing forms to scale up without proportionally increasing weight. The way something looks is inseparable from how it's built, how it performs, and how it manages stress.

You also see this principle working in reverse: undulations resolving into simpler, more robust shapes to manage structure. Sea fans grow elaborate branching networks of undulating fronds that concentrate down through progressively simpler geometry to a sturdy central stem anchored at the base. It's like an arch where the curved, expansive ceiling funnels loads into a concentrated columnar support. What draws me to undulations is that the relationship between expressive and controlled edges embodies this principle.

Photo: Amy Lyon Smith

The Aesthetic Challenge

This same relationship between free and constrained edges is what compels me in my sculptural installations: the tension between a very pure geometry and a more expressive sculptural form—formal geometry like a datum in a building or the square of a skylight, and something much looser and organic that emerges from it.

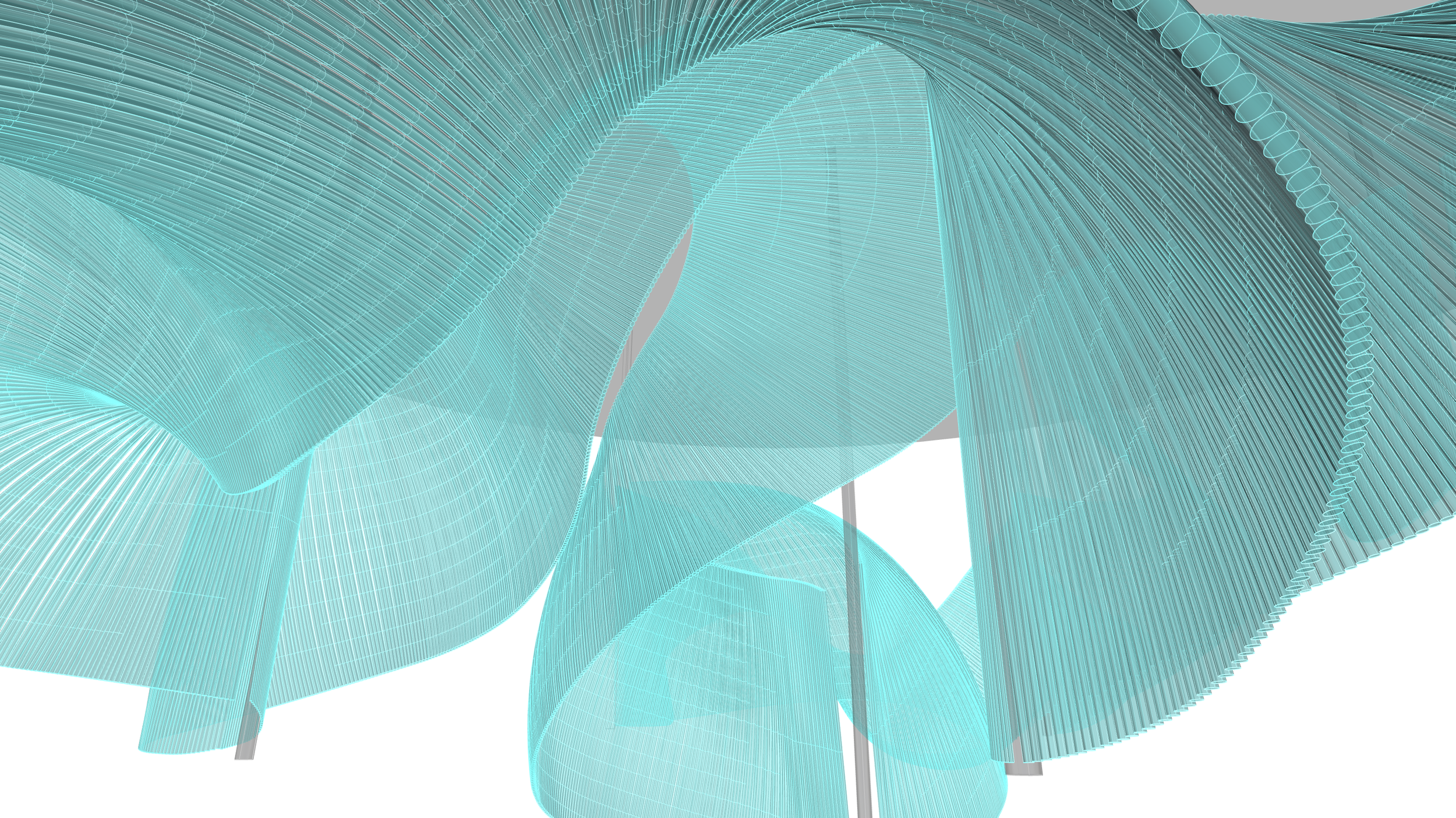

What's compelling about undulations is how they handle both needs at once. When one edge is shorter and the other longer, you get aesthetic complexity on one side and a simpler, more controlled side that naturally lends itself to structure—managing load, attachment, and the realities of building. Because installations must speak to their surroundings rather than exist in isolation, this becomes a language for connecting sculpture to architecture: the expressive edge can move and curve freely while the rational edge ties the work back to the building.

Bar Agricole: Putting It into Practice

The installation's billowing bottom edge looks wind-blown, but it's tied into preexisting square skylights in a historic building. Aesthetically, it's that tension between the pure rectangle and the wild bottom edge that makes the piece work. It speaks directly to this idea of constraint and expression.

But it also gave us a way to have a really strong connection to the building that could anchor the form in a way where it looked like it was growing out of the building and was integral to it. The shorter, more organized edge becomes the structural interface—handling load distribution, attachment points, safety requirements—while the longer edge gets to be sculptural and free. It's not just conceptual tension, it's functional division of labor.

At Bar Agricole, we achieved that elongated form by tearing at the corners—the material stretching and splitting to express the difference in edge lengths. It was made from a single layer of tubes, which limited how we could control the undulation. The tears themselves became part of the expression, a direct visualization of one edge being forced longer than the other.

Developing It

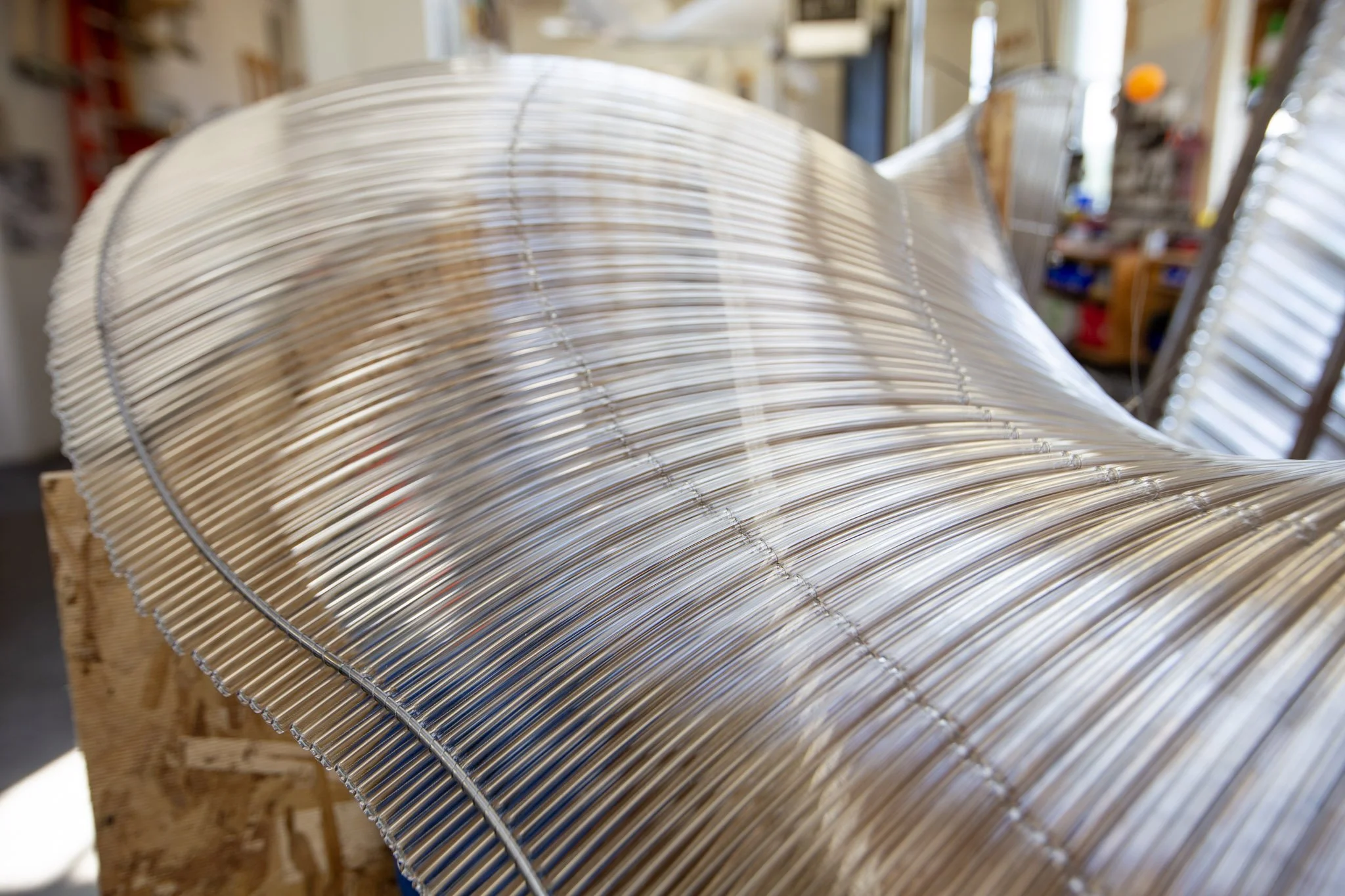

Having recognized what was really at work in the pasta—the importance of different edge lengths—we began exploring how to express that principle more directly with our glass fabric. Instead of relying on tears, we worked toward a system where one edge was a single layer and the other was doubled, yielding different edge lengths.

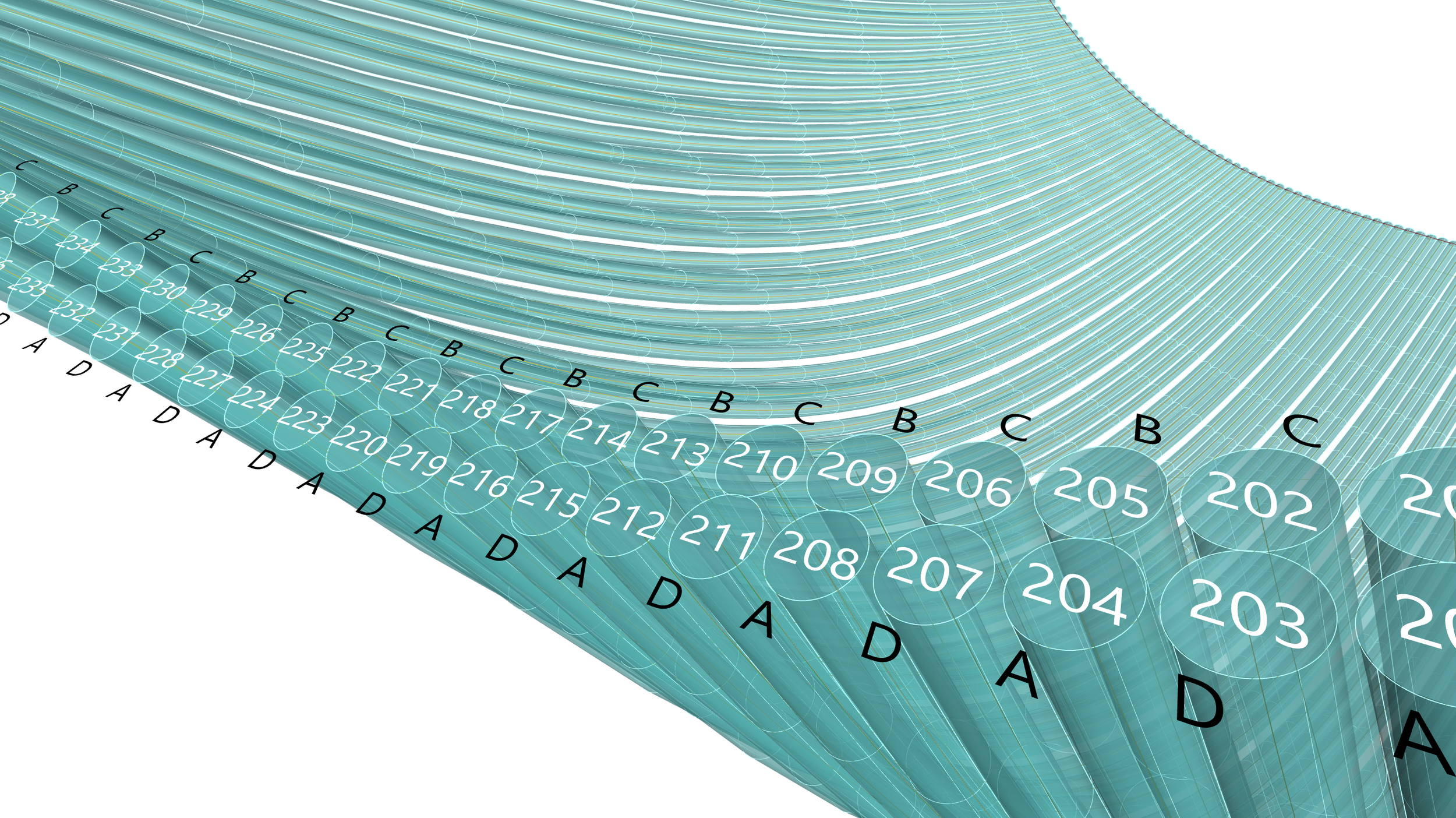

What seemed simple became profoundly complex. In a curved surface, adjacent tubes that should have similar radii actually don't—one must nest inside the other as they approach the shorter edge, and we started seeing systematic problems: tubes breaking out in pairs or quadruples, creating jagged edges instead of the smooth undulation we wanted. We measured every tube against the planned cut lists, looking for patterns in the deltas, running what amounted to forensic data analysis. It turned out the main culprit was "spooning"—how tubes nested at the stacking end—and tubes with more extreme curves spooned worse.

We developed scripting that dynamically predicts and corrects for this based on curvature, and we started building in stronger denoting of elements—tracking stacking order and unique tube numbers—so we could precisely manage these variables and generate adjusted cut lists. The technical complexity—pulling together CAD scripting, weaving techniques, quantitative analysis, theoretical geometry—shows this wasn't just surface-level imitation. We thought about scrapping it a couple of times because it was so difficult to solve.

But we kept at it because we recognized something fundamental was at stake. The result is something like DNA for shape: a set of rules governing how the material behaves, allowing different forms to emerge naturally according to those constraints. All this complexity exists in service of a single goal: making the piece look natural and effortless, as though it simply grew that way. These complications are critical exactly so the result seems automatic. Whether it's extruding pasta through a die, a leaf growing with differential rates, or our glass fabric system, it's all about the same thing: designing the right constraint to generate the right kind of form. The constraint isn't limiting the work—it's enabling it.

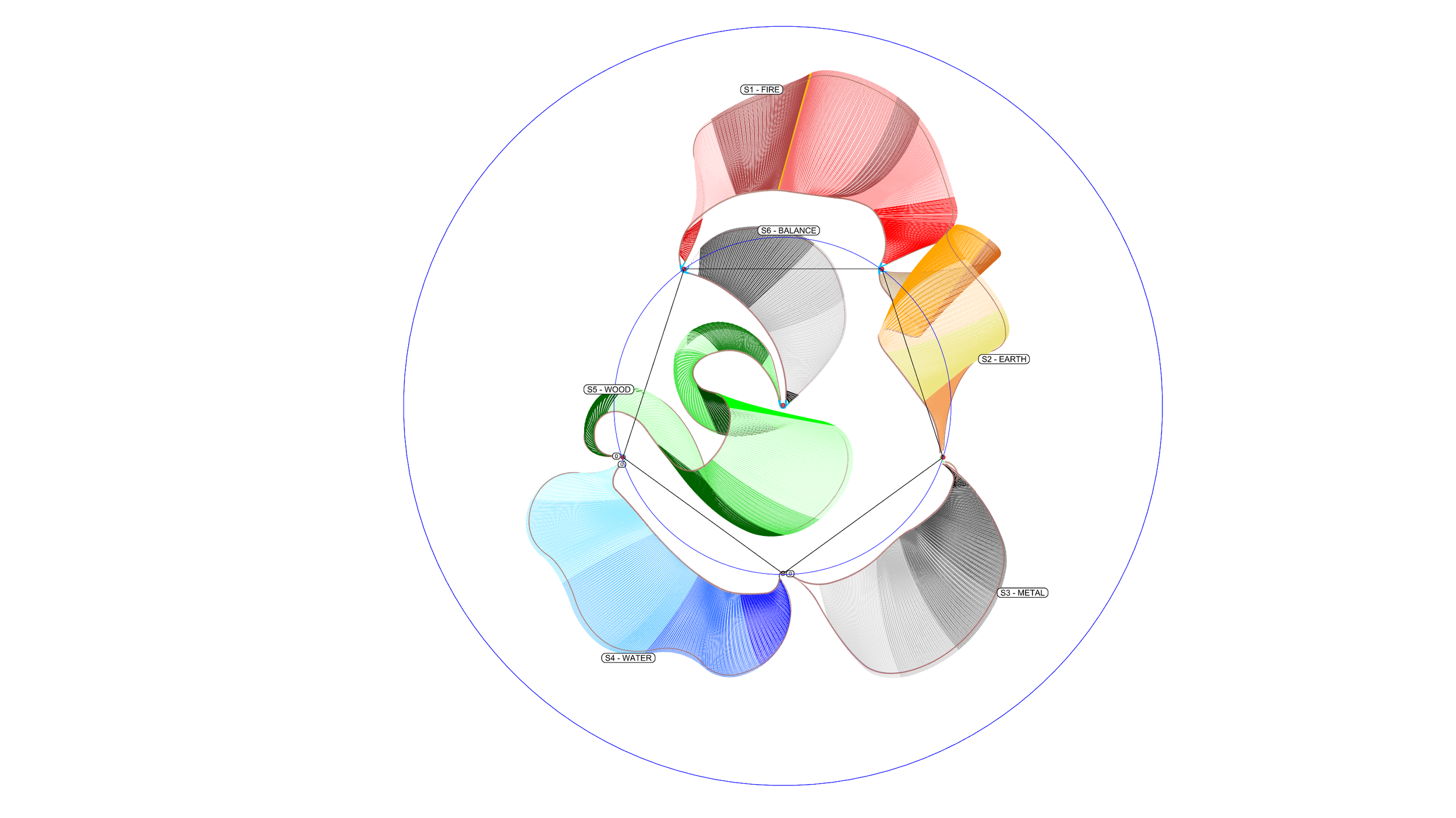

Opus Redux - Undulation V1

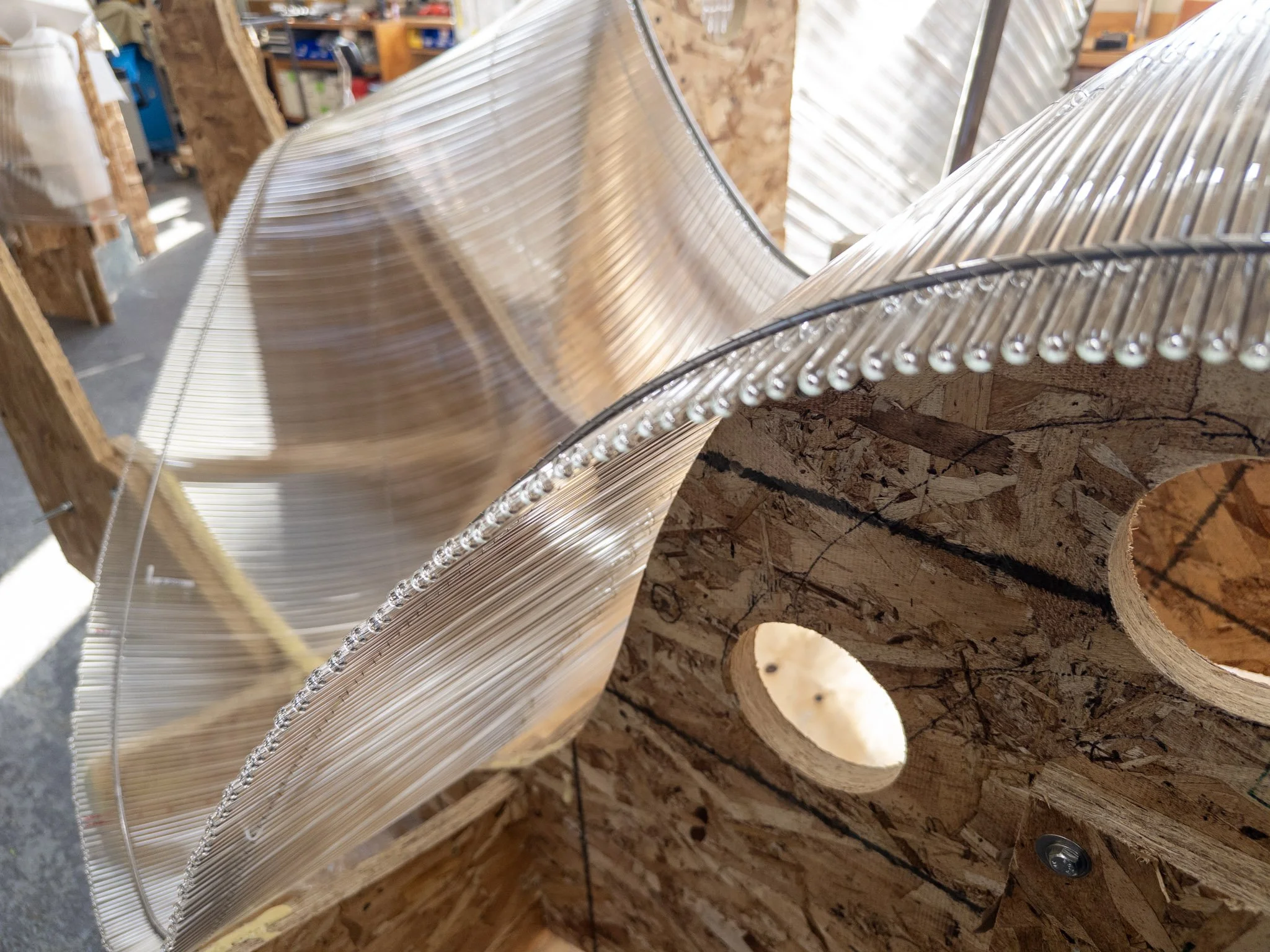

We'd previously created the lobby installation when the Opus development opened—Gehry's first project in Asia and a significant milestone for Swire Properties. When we returned to create a piece for one of the residences, it became the first work built entirely around this undulation discovery. It's organized around the pure geometry of a pentagon—or more precisely, five masts circumscribed on a circle. At each corner, a mast comes down from the ceiling, and the piece appears to be blowing and billowing up against these anchor points.

You can't see the pentagon explicitly, but it's there, organizing everything. The structure is part of the sculpture and essential to its basic shape. At the same time, the shape is very much alive and liberated from it—it looks like it's blowing up against those constraints and breaking free.

This relates directly to the circular alcove it sits in, which connects to the curvilinear language of the building. It all starts with very simple Euclidean geometry, and then you build from that and start a conversation between the sculpture and those structural points. The piece has a lot of structural integrity, but it's also grounded in a basic geometry that gives it coherence while allowing it to feel dynamic and free.

It shows the full evolution: from observing pasta, to understanding the principle, to solving the technical problems, to building something that embodies both the aesthetic philosophy and the practical engineering requirements.

In the end, it's about clearly defining the essential constraint, because that underlies the entire process.

Glass pasta coming your way soon.