Imagine our delight when we were contacted by Manuel Fadat, a French curator, researcher, critic and teacher who "geeks out" on technology as much as we do. He works for Oudeis—une laboratoire pour les arts numériques, électroniques et médiatiques aka a laboratory dedicated to the digital, electronic and media arts. And the fact that he’s from distant lands confirms our prejudice that very few people in our own country know we exist.

Manuel has included Nikolas in a series of interviews he’s done about the links between glass and digital technologies seen through a variety of lenses. The Oudeis website, which functions as a hub for artists specializing in digital, electronic and media arts, has a wide variety of information about people and goings-on in the field the world over. From exhibitions and artists to residencies and whatnot. All of the interviews published in this series can be seen here.

Rather than copying the entire interview I’ve pulled a few questions and abbreviated the answers.

Manuel Fadat : First, as an artist, as a designer, what is the relationship you have with “technologies”, in general?

Nikolas Weinstein: The design of my installations is driven by an interest in sculptural forms and how they relate to architectural space. Technology has nonetheless become a principal element in my work. Tools are things that I develop to solve problems rather than parameters that define what I think I can do…. It is only as I approach the completion of a project that I finally appreciate how to really build it. The majority of the project time is spent making mistakes and learning, and the actual fabrication of the work represents only a small fraction of the effort. The solution gives me new ideas. A completed project is an opportunity to see what has been made possible by the new technology. And so the aspirational cycle begins again, and I design new problems to solve.

MF : Which new technologies do you use and why did you choose these new technologies ?

NW : Aside from the custom kilns that we build, we use a lot of computers in our work. The backbone is Rhino 3D, a CAD package with Grasshopper and Kangaroo plugins. Because the installations are principally about the architecture and because the sculptures themselves have a lot of “irrational” or “complex” surfaces, this is a good environment to match organic shapes to built structures. This allows us to do a great deal of analysis on huge sculptures that we can’t fully mockup prior to installation. We can map their relationships to the building very closely (connections points, etc) as well as break the sculpture itself into “digestible” parts such as cut lists for thousands of unique tube lengths, construction maps for molds, and cable lists with corresponding data.

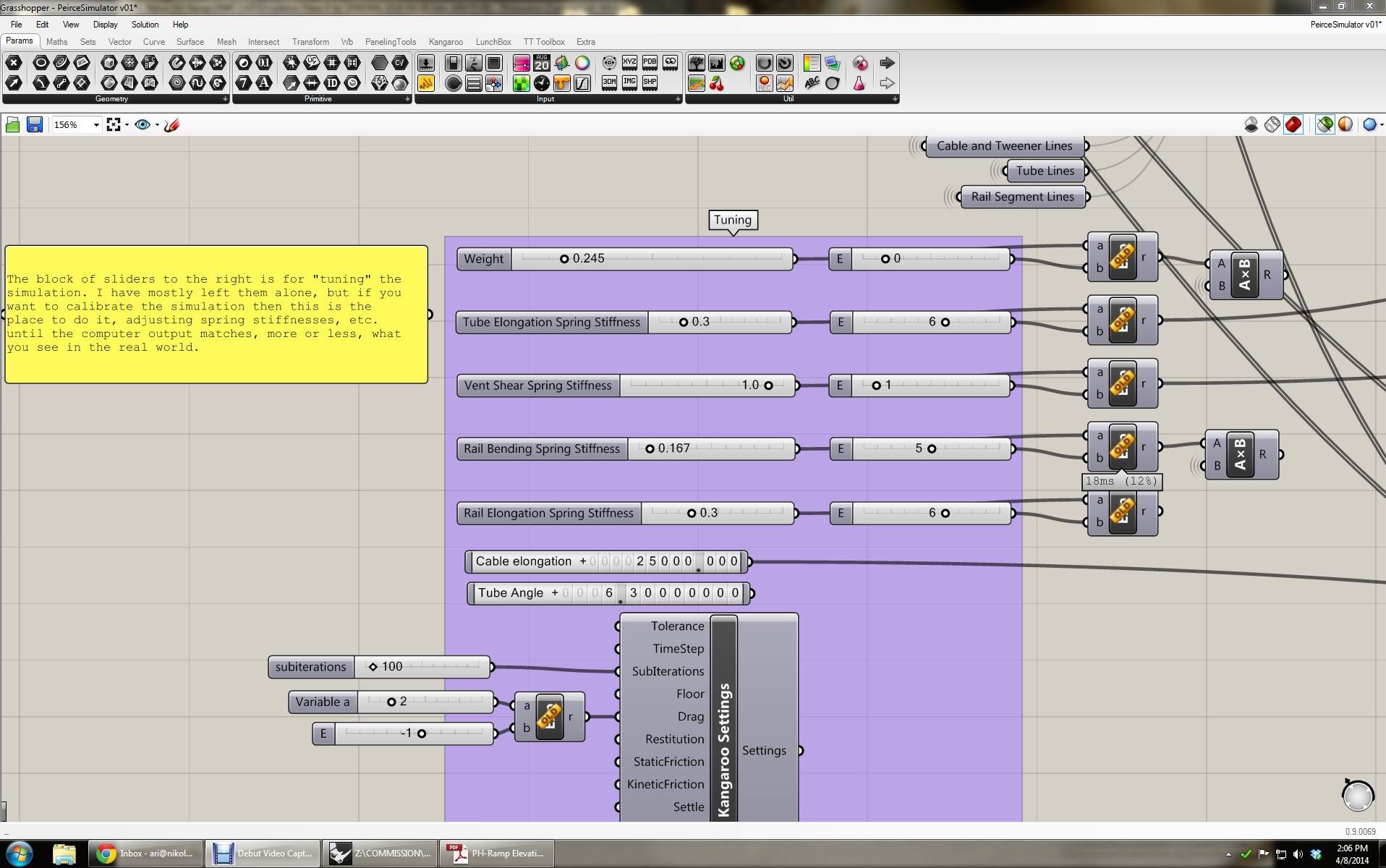

An overview of the Grasshopper programming interface, which uses a visual—rather than traditional—

An overview of the Grasshopper programming interface, which uses a visual—rather than traditional—programming interface.

MF : Can we say that new technologies influence the form, the meaning? Or they are tools, only?

NW : Yes, I think this is especially true with glass as a material because it's so technically challenging. It's really hard to blow glass and it's really hard to manage annealing complex forms. I think this challenge sets a high threshold for entry and this is one of the reasons why there's not a huge body of highly technical and refined glass art. It takes great effort to get ahead of—and on top of—technology before you can say what you want to say aesthetically or conceptually.

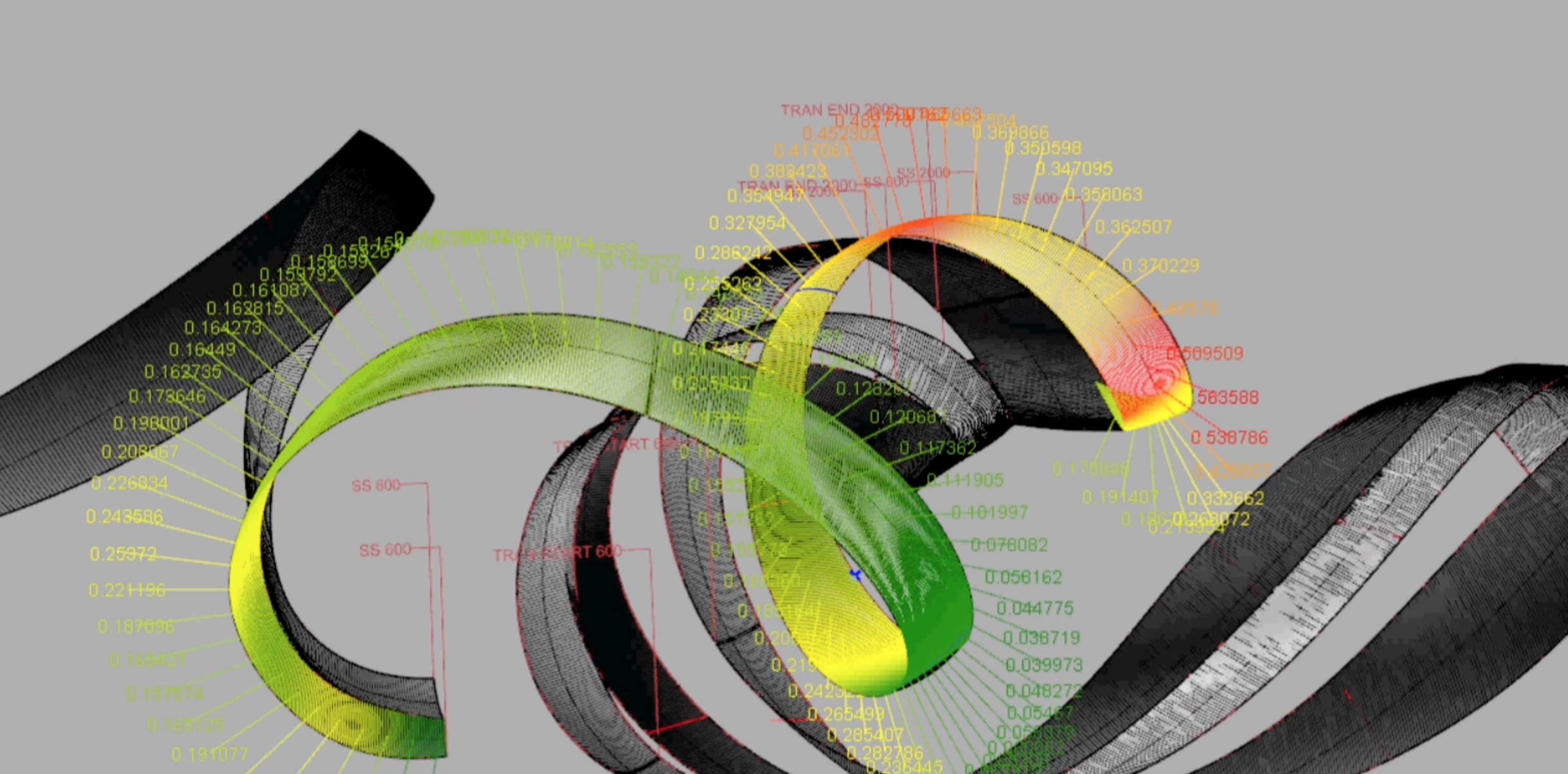

Custom Grasshopper software written to visually describe, analyze, and prevent gaps between neighboring glass tubes on curvilinear surfaces.

Custom Grasshopper software written to visually describe, analyze, and prevent gaps between neighboring glass tubes on curvilinear surfaces.

MF : What do you think about the use of new technologies (digital technologies, new media) in glass arts and design?

NW : I think there's a huge divide between the industrial and the studio world. Most of the technology available to glass artists is relatively neolithic compared to the highly refined world of industry. I believe that there needs to be a lot more technology and engineering introduced into using glass outside of large commerce. That’s a tough sell and one that’s difficult to underwrite, but I think it would make a big difference in what one is able to imagine doing. Conversely, studio artists are much more agile than large enterprises and they can introduce ideas that corporations would take years to develop much less ever conceive.

This detail shows the adjustable parameters of the sculpture material within the custom Grasshopper software.

This detail shows the adjustable parameters of the sculpture material within the custom Grasshopper software.

MF : May be could you give us some relevant examples of artists, designers, works or experiments ?

NW : I always loved Alexander Calder for his playful creations (the wire trinkets and toys) and for his appreciation of physics (the mobiles). I’m a big fan of Richard Serra mostly for the minimalism and his adage that the final work must express the way in which it was formed - that you can almost feel the pressure and tension applied by the rollers through which the plates are worked. I also like a lot of the art machines that are being built today, like Theo Jansen’s Strand Beests that have equal measures of poetry and mechanics. These artists are all interested in animation, whether it is by natural forces or mechanics, and that’s what I’m interested in. The technology is just a tool that helps to make glass that looks like it’s "alive."

Here is the interview in its entirety. Scroll down for the English version.