Each season takes one down. Sam was the first to go about two falls ago and stayed home hacking and wheezing on some Friday or Monday. When you're puttering away at the shop, it's easy to imagine your fallen comrade prostrate and staring at the ceiling grateful for the day off but frustrated with the hobbling effects of some flu.

Away from the grind of the shop and given better health, I would normally imagine Sam cycling through the hills of San Francisco on one of his umpteen bicycles or watching a Formula 1 race on the other side of the world in some local bar surrounded by like-minded freaks. Yes, there is apparently a San Francisco Formula 1 club that meets regularly at bars to watch cars lap a track over and over again.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6V_IesA-dA&feature=player_embedded

Before joining us at the Studio, Sam was a Competition Manager at an improbable outfit that specialized in developing zero emissions Formula 1 cars. I know. It seems to be a whacky combo, but I suppose there would be some pretty interesting engineering problems to solve. And before that, he was a Race Engineer at Racers Edge Motorsports, Inc.. Some toss about the term "gearhead" in reference to geeks with a penchant for mechanics. In this case, I think we can all agree that Sam would make a fine poster boy... especially considering that he makes scale Lego models from scratch of things like the Le Mans Prototype Ferrari.

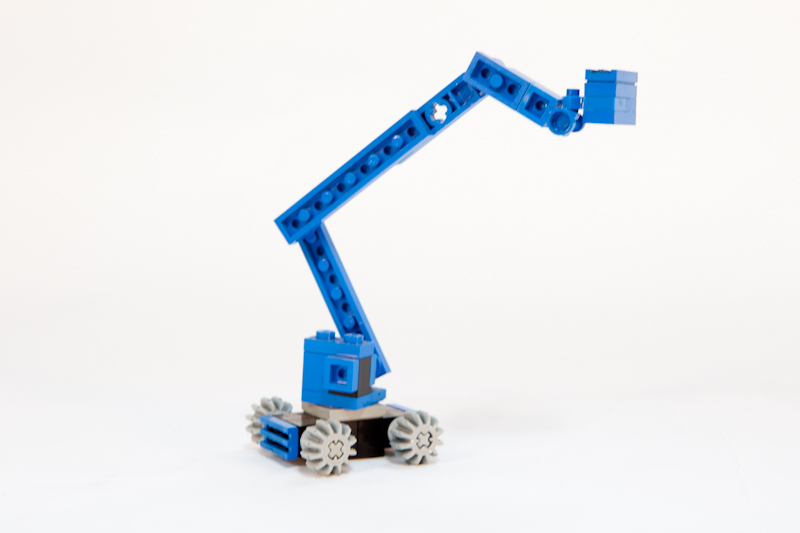

The fruits of his extracurricular tinkering began to appear around the shop. Something on a sideboard in the conference room or beside a machine down in the shop. Each was a miniature and often functional version of the real thing. One was a version of the articulating boom lifts we use during installations. He also made a copy of the chop saw which lived beside the real one for quite some time:

Sam found our way to us via Ari who went to high school with him back in Jersey. That makes three Jersey boys in the shop, including Steve. And when we were scrambling to find people to help install the Shanghai job, he threw caution to the wind and joined our merry band overseas. We took about ten people to China for a month to install that beast. And the dear boy, Sam, stuck around. And besides what he does at work, what he does at home while sick is perhaps his most remarkable and enduring trait.

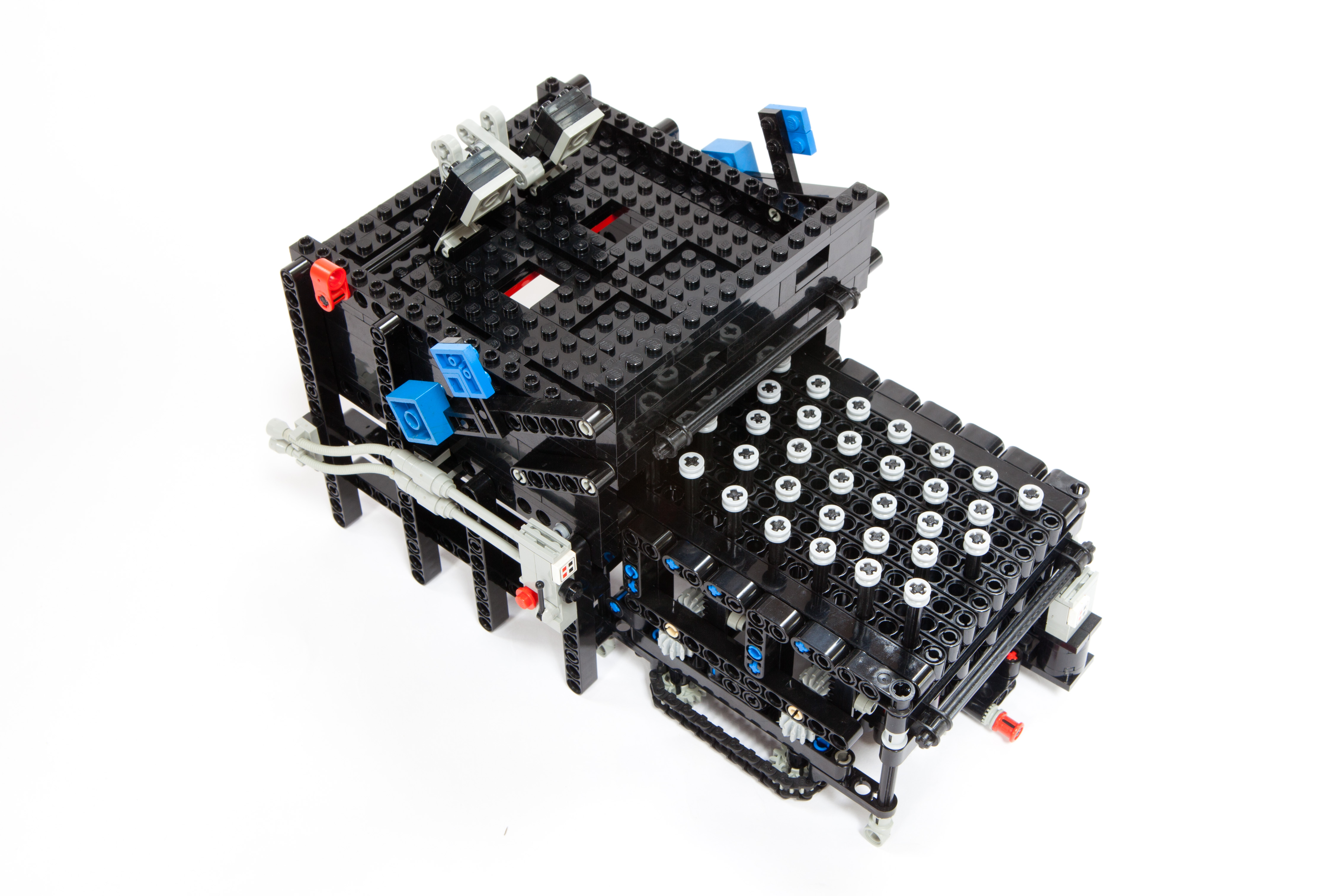

So on that autumnal day of recuperation two years ago, Sam was way too bored and decided - clearly in the high delirium of fever - that he would busy himself with making a scaled and fully-automated replica of the giant kiln that sits at the rear of the shop. The "Kettler 0898" was affectionately named after the German team leader who helped to install our first project in the Gehry building in Berlin. He smoked excessively, kept us up until all hours, and loved fast cars. God bless him. And as I write this post, it only now occurs to me that Kettler and Sam must be some long-ago separated karmic twins - both bedazzled by high-perfomance engines and velocity.

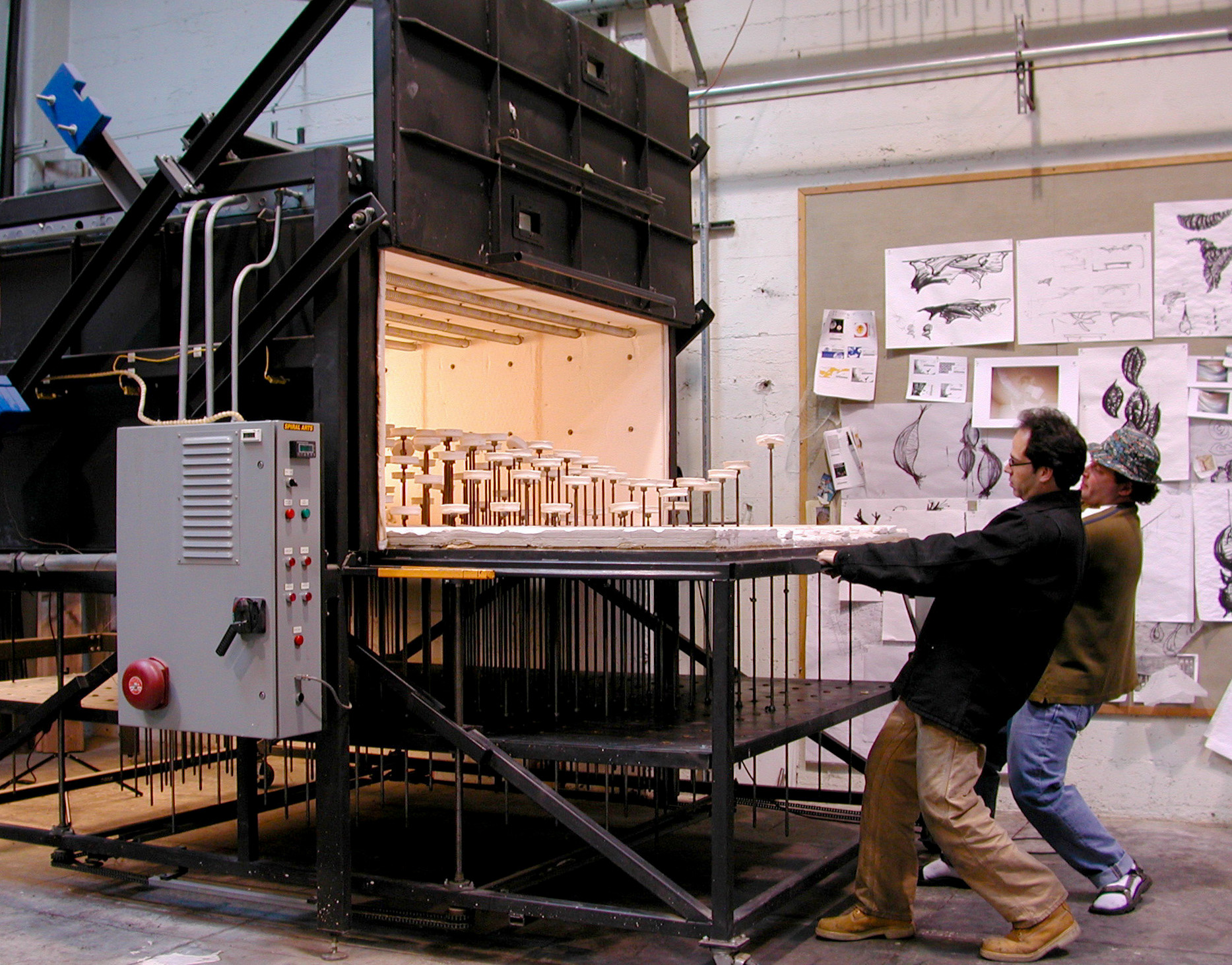

When I designed that kiln, I too was twinged with a sort of fever, though mine was induced by wine and an overwhelming sense that I was in way over my head. I was 26 and had never made anything much bigger than a person. The commission would weigh over two tons and I admittedly had no idea what I was doing. Long story short, the thirty-six car-sized sculptural elements were fused assemblies of glass tubes that were then bent into curved panels. The process took two grueling and time-consuming steps and threatened to require two separate kilns of considerable size if we were ever to stay on schedule. And we were already way behind schedule.

So one night, I sat with a bowl of pasta drinking my way into oblivion when I remembered those toys with hundreds of little pins. If you pushed your hand against them, the pin heads registered the shape. I had recently seen a large version down at the Exploratorium Museum in San Francisco (for those who have never been, go). So I began to imagine a giant machine with automated pins that would grow out of the kiln floor over time. This allowed one to lay out all the tubes, bring them up to fusing temperature (at which point the individual components stuck together and now acted as a single element), and then incrementally introduce one-off topographies at the same rate that the glass was bending. This got rid of huge molds and their associated construction time and thermal mass. It also meant that we could collapse the two processes into a single firing. I sent the napkin sketch to a crazy and inspired mechanical genius up in Seattle who ultimately built a prototype in about a week and then produced the final kiln that was trucked down to the shop from Seattle in an eighteen-wheeler some months later. The rest, as they say, is history.

Back to Sam. So this is the Lego machine that he built when afflicted with his own sickness. Sure the scaled version from memory is cool. But the fact the he made it work with all those little gears and chains is insane!

For years, I have wanted a little time-lapse video to use in lectures to help people understand what I was talking about. Now we have something far more extraordinary: